A project involving the rotation of the entire visibly physical collection of an art library in St. Gallen, Switzerland that utilizes RFID technology allowing for a perpetually shuffling wall of books predicated by public use and self re-shelving. Each volume remains accountable through radio frequency tracking. This rotation relocated all books found on the ground floor to their equivalent corresponding positions on the mezzanine level shelves and vice versa. This architectural flip exposed the degree to which this space, however non-categorical by design, continues to retain certain systemic ordering structures that are tethered to a conflated impression of access to knowledge production via disparate human labor and its erasure.

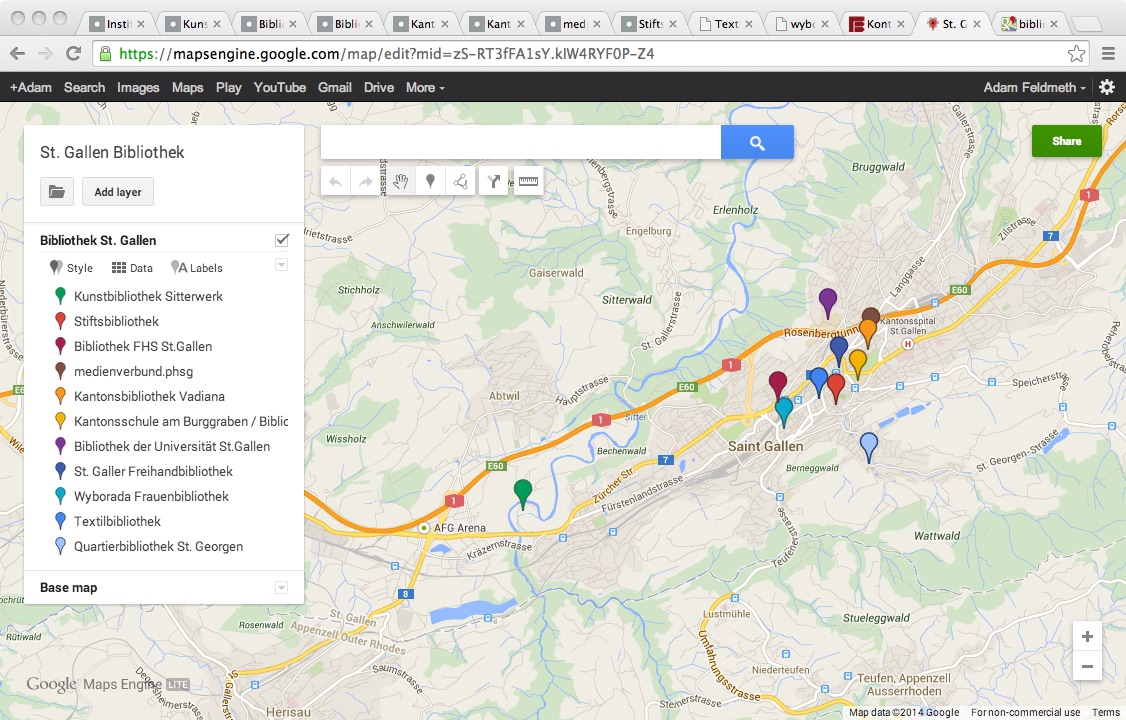

The project was realized in Sitterwerk, a non-profit cultural institution, which houses the Kunstbibliothek, a reference library specializing in art and related fields of interest. The holdings largely come from the book collection of Daniel Rohner (1948-2007), a man who amassed some 25,000 titles, primarily of exhibition catalogues and monographs in art, architecture, and relevant theory from the second half of the 20th century onward. The space is open to the public as a reference library. St.Gallen, the city, has the moniker "Buchstadt" due to its history of book keeping. The oldest library in Switzerland and one of the oldest monastic libraries in the world is located in the city, the Stiftsbibliothek. This has subsequently compelled other speciality libraries to develop among public branches, university, and communally organized collections.

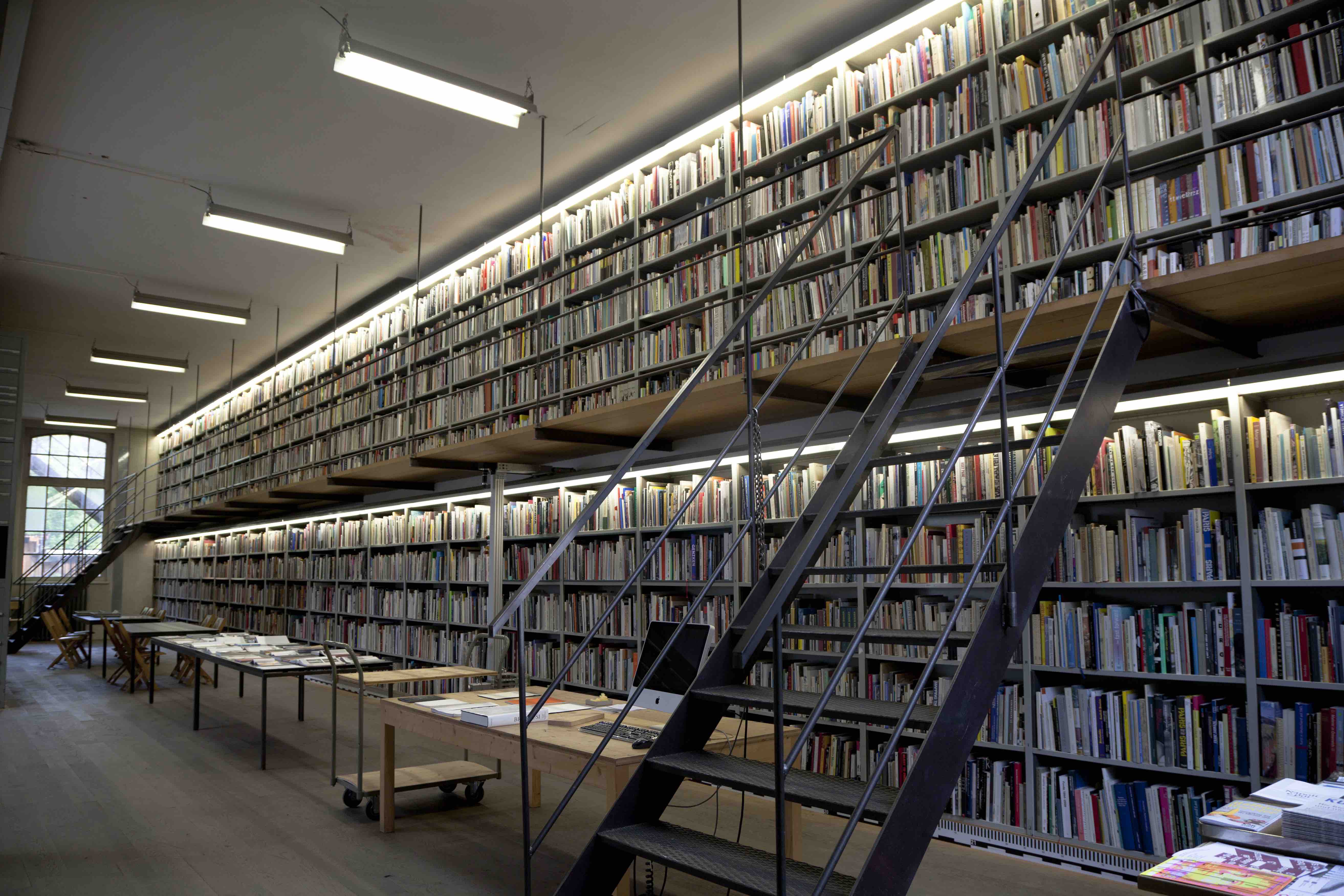

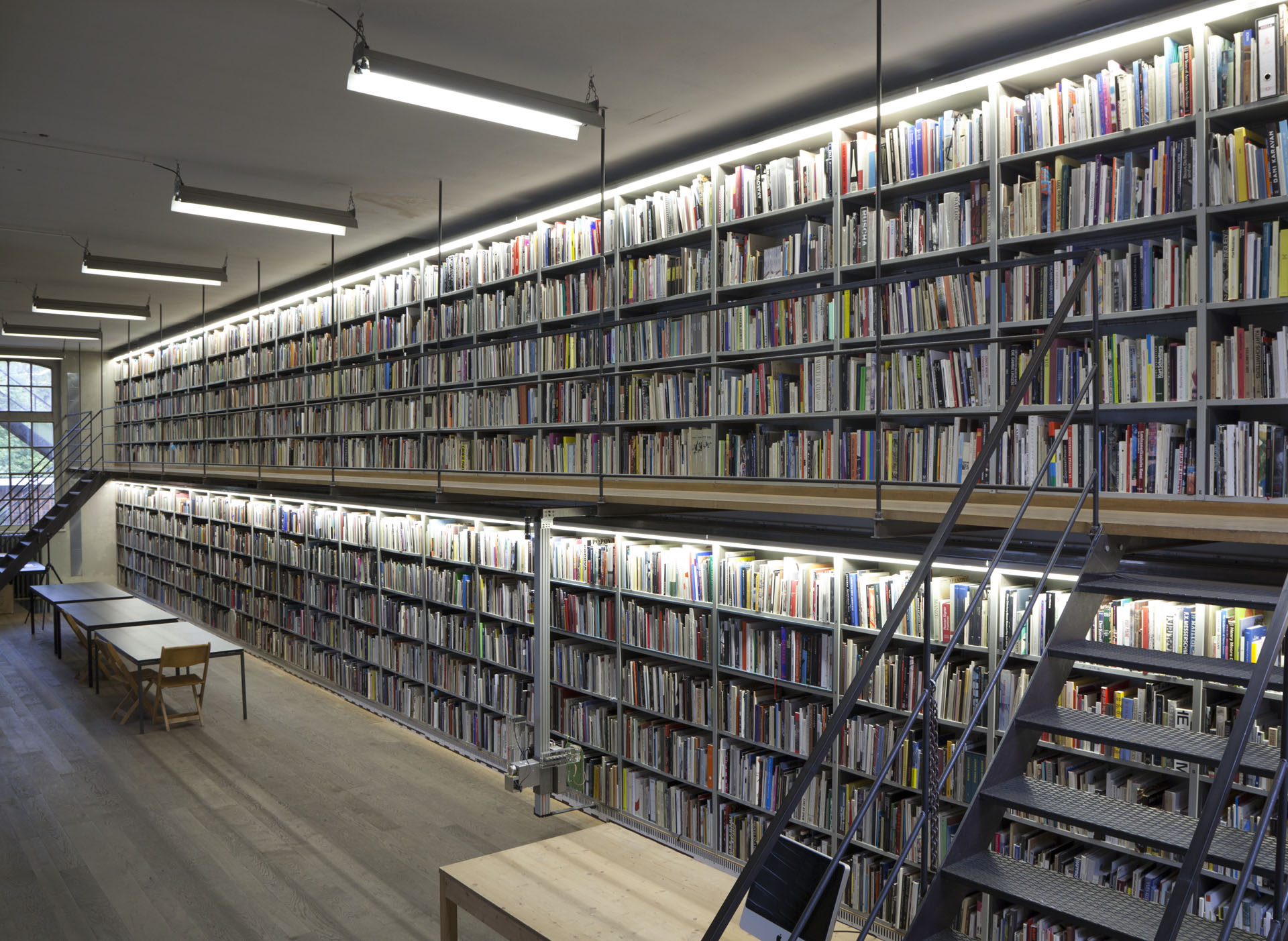

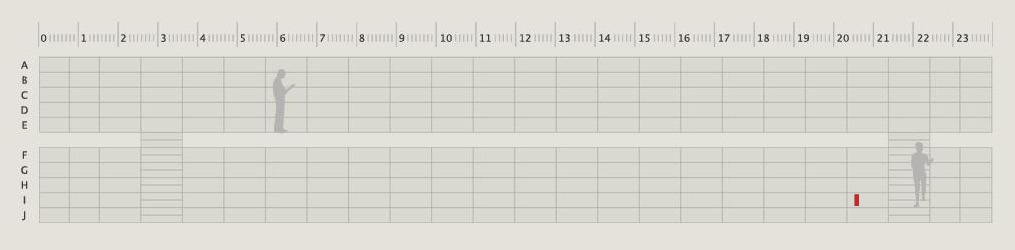

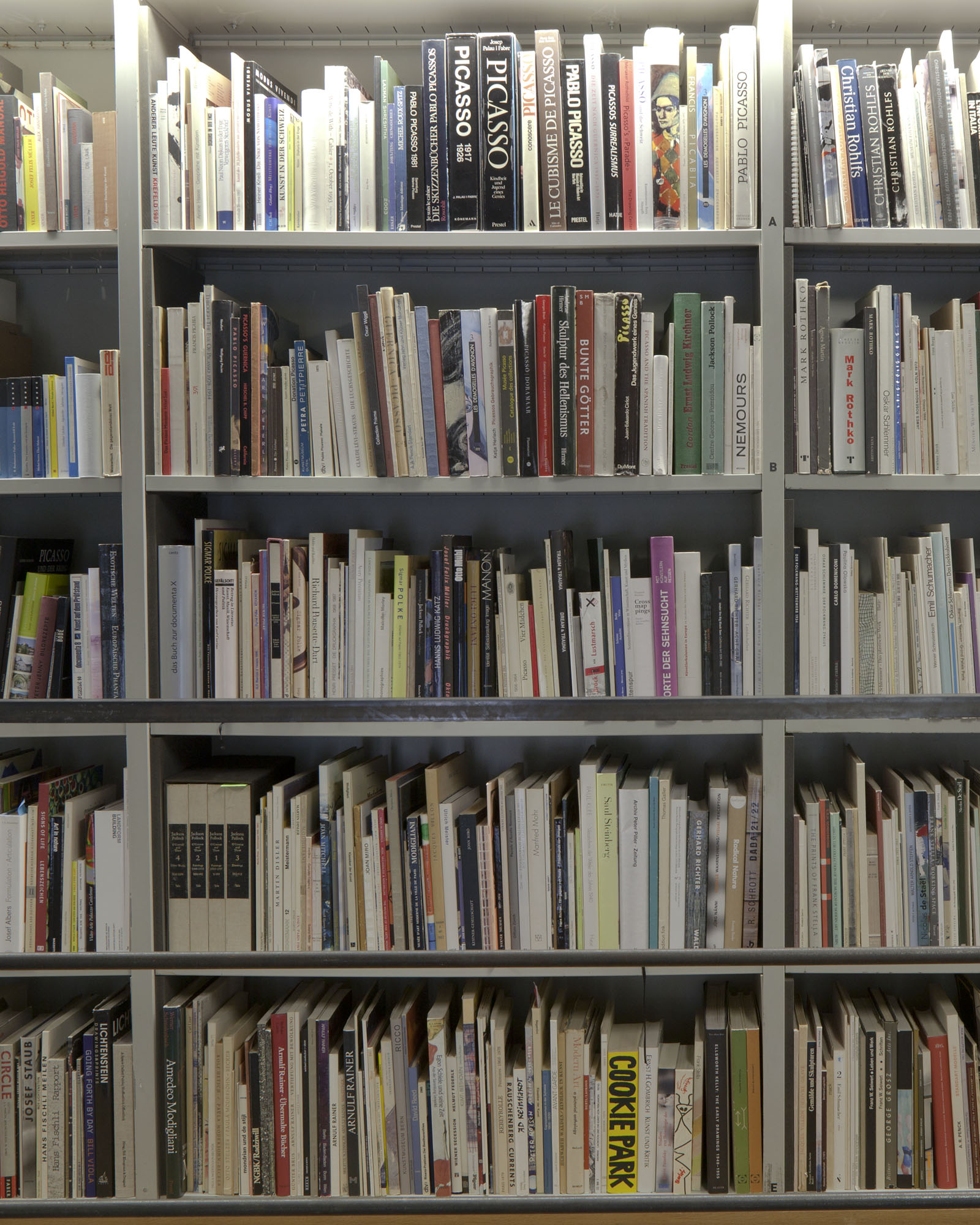

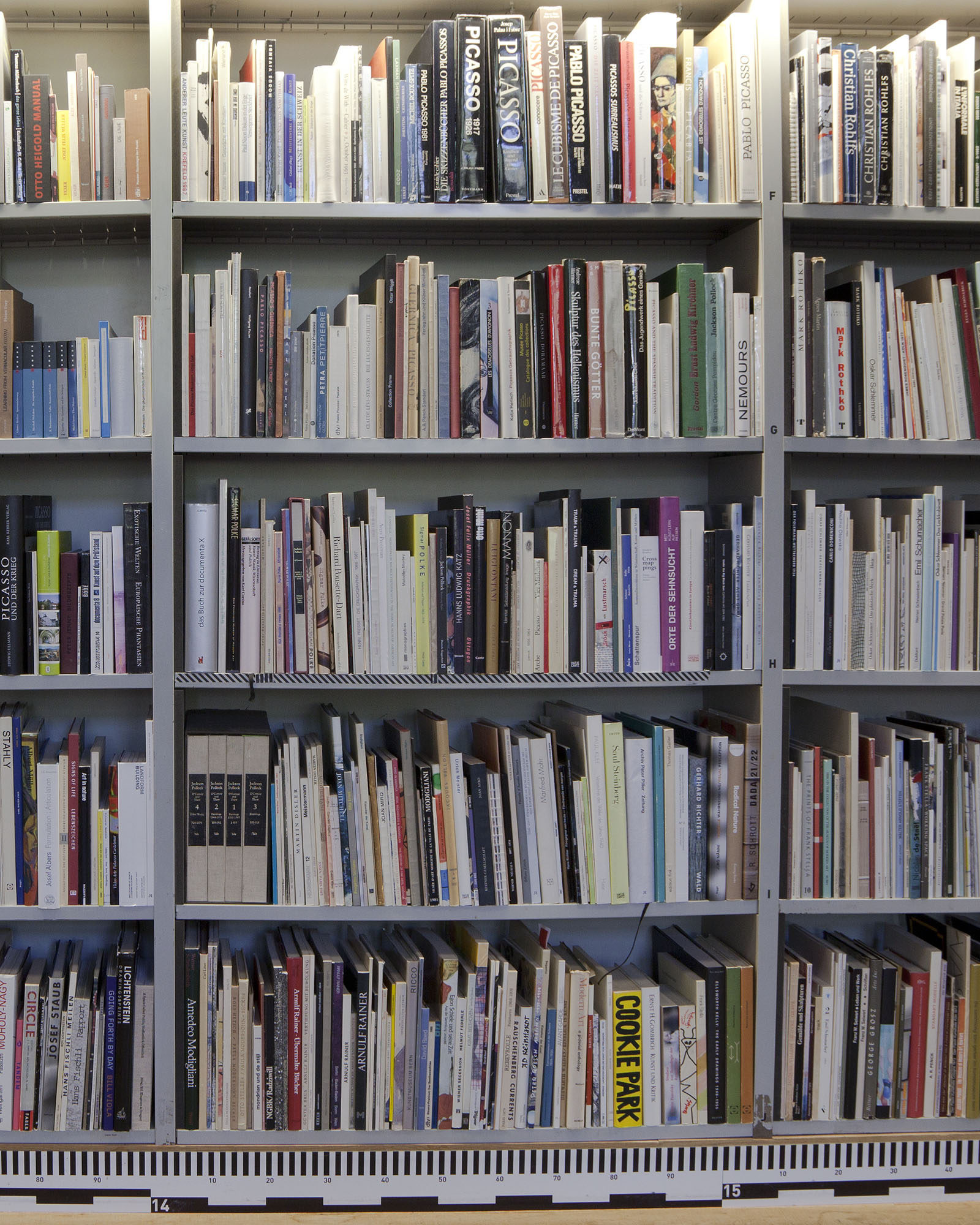

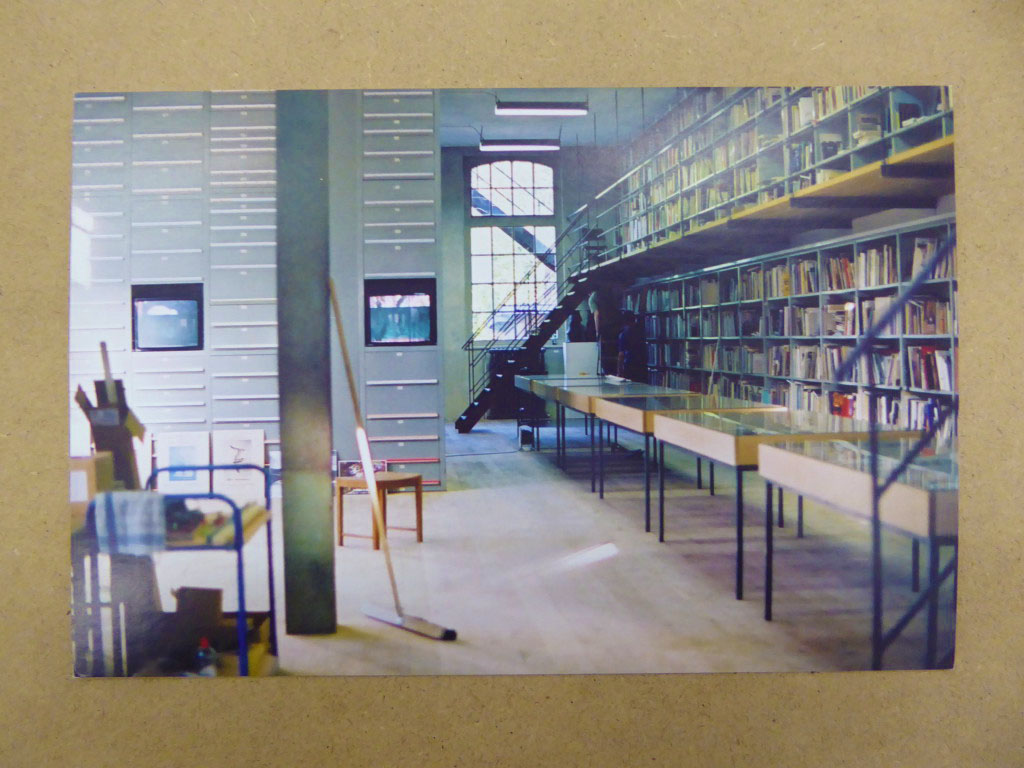

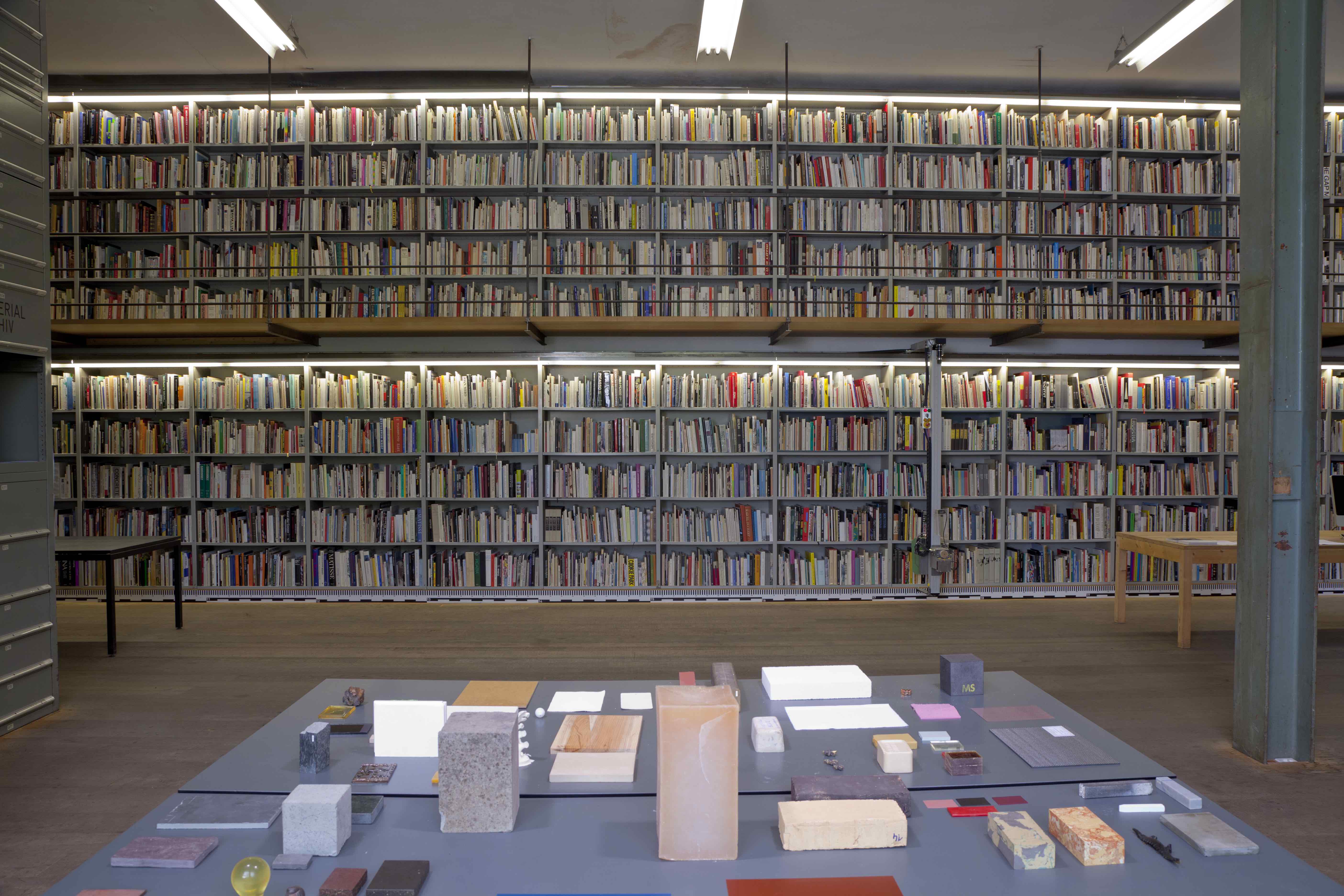

The Sitterwerk library is administratively connected to and located within the same complex as an art fabrication foundry, the Kunstgiesserei, which is located in a small valley, called the Sittertal, along the Sitter River. The repurposed complex of buildings were previously a site used by the local textile industry. The Kunstgiesserei has helped to fabricate works for a wide variety of internationally reknowned artists: Fischli/Weiss, Urs Fischer, Katharina Fritsch, and Paul McCarthy among others. The art library is accessible to the public in a 24 meter long room, the bookshelves extend along the full measure of the south facing wall. The other half of the room holds two offices, a bedroom for visiting researchers, and a nearly ceiling-high, custom-built filing cabinet system which stores a material archive. As the foundry is working with a variety of materials to help produce and restore statues and all kinds of contemporary sculptures, they keep this inventory of material samples that can be referred to when foundry craftspeople are troubleshooting a project in development, as aids in occasional workshops hosted by Sitterwerk, and for use in independent study for public users. The "book wall", has been architecturally designed to incorporate a bifurcation, effectively two levels, shelves which run along the ground floor and reach half way up the structural wall and an equivalent set of shelves running along a mezzanine that is accessible by stairs at either end of the room.

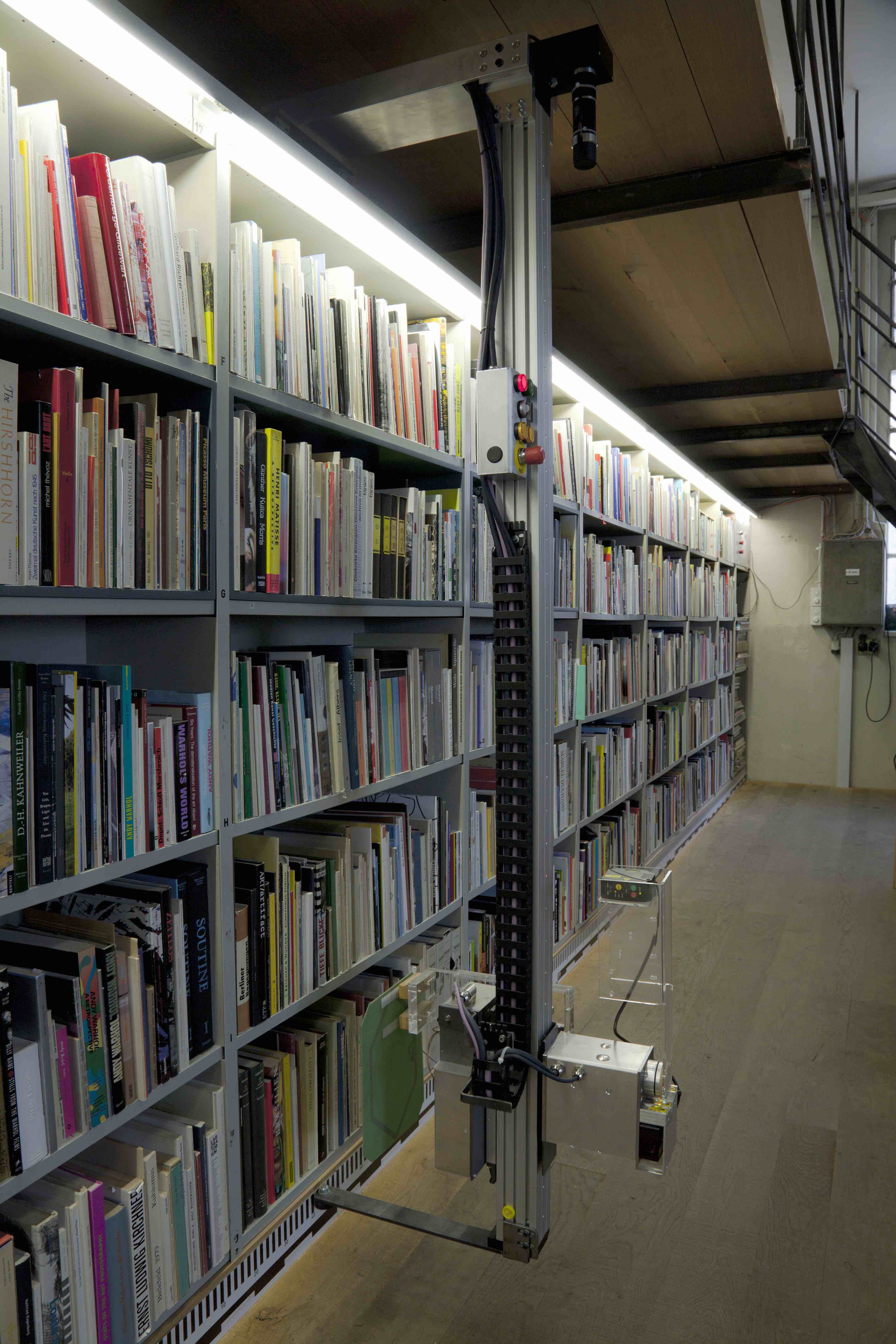

The project involved considering an unique system that this library has developed to distinguish its organizational premise directly through active public use. In an effort to encourage chance findings among the shelves when an individual may be in search for a specific title, "intelligent tags" have been installed inside each book. These tags are tracked by radio frequency. This allows the spines of the books to remain uninterrupted by the stickers and labels common to many library books. To track the visible collection, each level of the library is equipped with a device carrying a receiver for this radio frequency identification technology (RFID). The "RFID-reader" is attached to a mechanical guide which scans the wall of books daily, recording the position of each tagged book and its location in the bookshelves along the wall. What this creates is the possibility to place a book anywhere on the shelves after study irregardless of any specific shelf where a user drew it from.

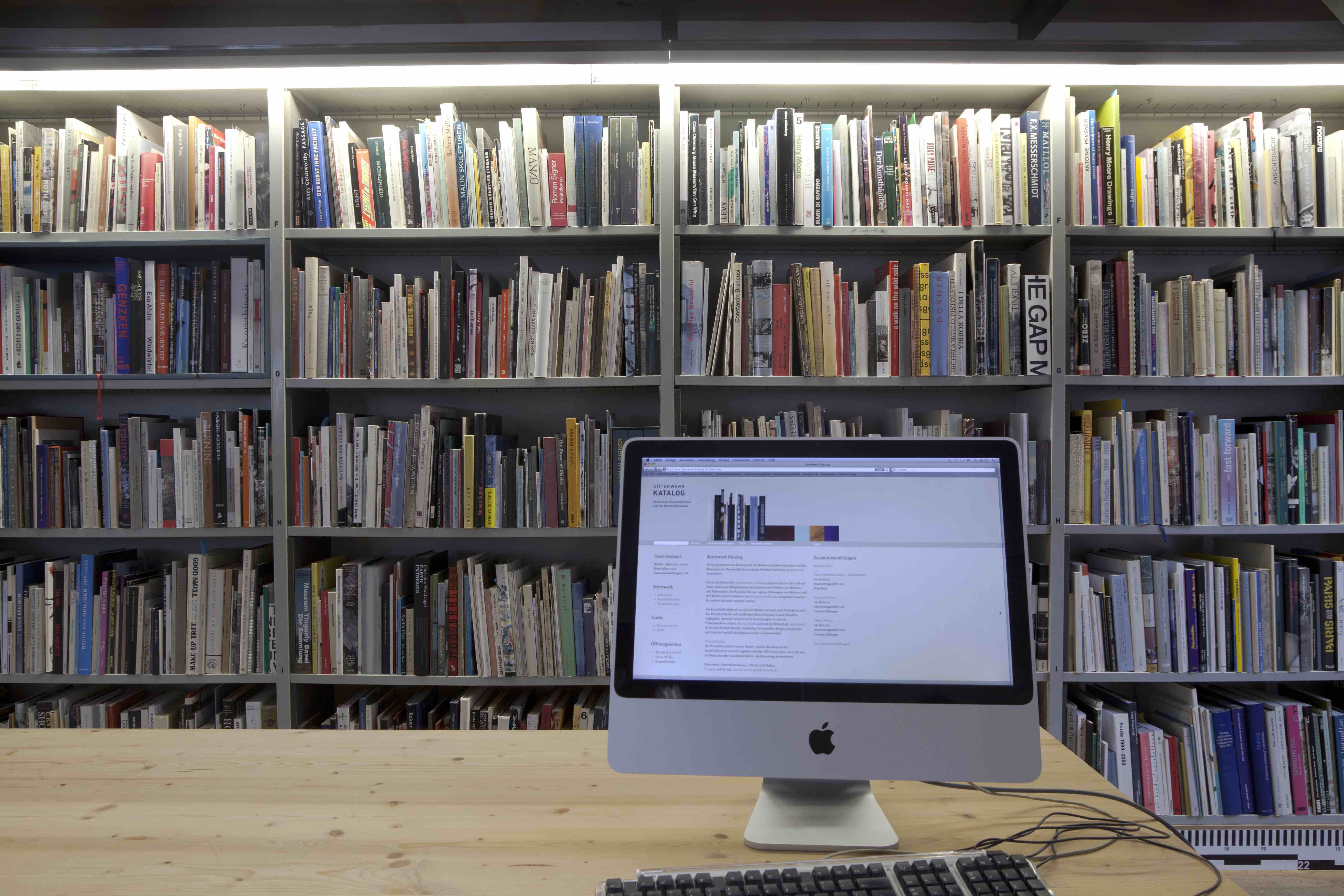

No Dewey decimal system or categorical divisions make the library a constantly shifting mix of documented art history. This shifting is perpetuated directly through the public use of the library. Randomness is generated through this yet also the opportunity for personalized subjective sub-ordering and curation. For instance, if I found twenty books during a day of research that I wanted to keep together as a set for the immediate future, I could place them altogether as a bundle on a free shelf. With no inherent safeguarding, this may possibly give a future visitor an opportunity to notice some curated relationships through the proximity of titles culled by another’s subjective research interests. These personal arrangements can be logged and archived on an online catalog which also provides a readout of all individual book locations through database searches tethered to all the standard search fields: keyword, author, title, etc. In addition to the RFID scanning, each book cover and spine has been photographically scanned into the computer. These visual facets are displayed upon searching for a title in the database. The flat, two-dimensional scan of a cover and spine contributes to identifying the three-dimensional book along the wall.

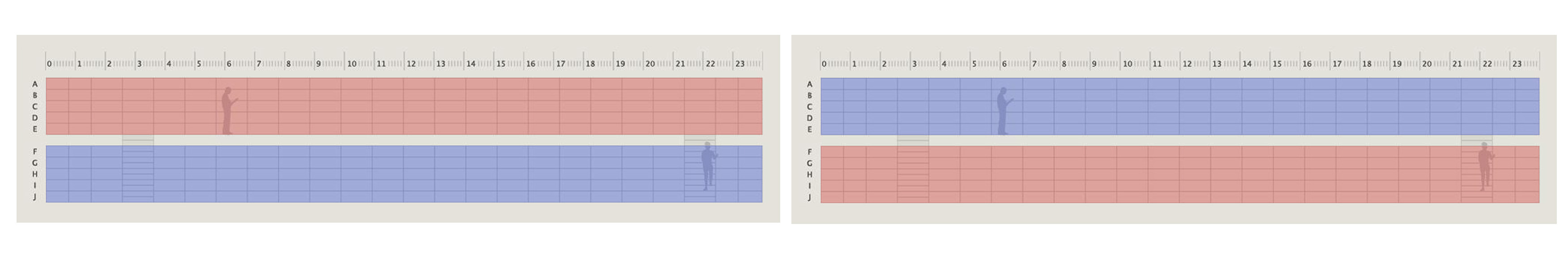

My proposal involved a rotation of the library's contents. All the books that were then located on the mezzanine level shelves exchanged places with all books on the ground level shelves and vice versa. This means that while all books moved up and down one level vertically, they maintained their exact horizontal positions along the wall. For example, the bottom row shelves running along the 24 meter ground level became the new bottom row on the mezzanine level, et. al. Importantly, this rotation did not disrupt the horizontality of any recent groupings arranged by library users, like in the example of twenty books previously posed, which seemed to be limited mostly to the curation of a single shelf. These curations are premised on personally organizing a (horizontal) shelf of books and thus the proposed rotation did not interrupt any intact arrangements.

The rotation took place during non-public hours over a two day period by a two-person team. This period of time was decided so as to not disrupt any users during public hours, temporarily close the library rendering it inaccessible, and not draw undue attention to labor involved as performance. This also ensured an exacting precision during rotation was more trackable without interruption or accidental displacement of any one book from its position along the wall. Rather than the public witnessing this undertaking, a person immediately after encountered all books already moved. Although it is a very regular experience to find books in different places along the book-wall, in this moment a person was capable of knowing exactly where every book was previously located, directly above or directly below the level, irregardless of what any of these books contained.

There are a number of contingent reasons for this movement, not the least being the proximity of the art foundry a few feet away where heavy material like bronze is worked with regularly. How does the proximity of this kind of raw material for art production at an industrial scale correlate to the library not only as information but also as a mass? The public who visits the library after the rotation was able to look at the wall of books and imagine the mass weight through holding portions of its contents. In this, I hoped to emphasize the materiality and weight of each book in hand. The library is designed to accommodate multiple micro-movements stimulated by users’ study, which in a single visit may only add up to a small quantity of books in hand. The RFID technology individualizes each book as an autonomous object within the boundaries of the internal architecture, the shelves. Through a decisive reorientation which imposes the architectural division of two levels onto the ever-mixing contents of the library, the books on each level are taken as a set rather than as discrete objects. In this regard, they effectively become representations of the the architectural ground level and mezzanine. While I do nothing which impacts the literal architecture in the space, the rotational gesture seemed to bring the mezzanine to the ground while it raised the ground up.

At the time of installation, I was interested in advancing a consideration I first had the previous summer: While books can re-enter the shelves wherever do to this institutionally self-described dynamic organizational system, I had factored that a majority of books re-enter the wall on the ground level bookshelves. This level is where the research tables are, where books would be carried for seated study. Even in instances when books are drawn from the mezzanine level shelves and brought downstairs, it is probable many of these books are not walked back up the stairs after study. Instead, they are placed in any conveniently open space in the most immediate shelves adjacent to the tables at ground level. By inference, this would mean that the majority of the interaction and mixing of the collection was occurring on the ground level, which exposes one curious limit brought about by the architectural design in relation to bodily access. Rotating the books of the mezzanine down both implicates and encourages a more substantial mixing to occur thereafter while also highlighting to the library as institution as well as to the library public certain dark corners among what is endorsed as a liberating space in the context of art historical knowledge.

Another aspect I happened to notice was a predominance of what could be categorically called sculpture related artist titles on the ground level expanse whereas there was a likewise predominance of painting related artist titles on the upper level. In this, there was a symbolic exchange that occurred in switching these once historically discrete categories and reversing what sits on top of what when stepping back and observing the library en masse along the vertical plane. Taking up the entire space of one interior wall, the books present the qualities of a graphic collage as well as a wall of bricks. The scan flattens them into a two-dimensional collage built of three-dimensional book objects.

The library is available for public use as much as it is a resource for the workers of the art foundry and visitors pursuing focused studies. While some individuals will have a title or topic in mind to search for and go directly for the computer to isolate a particular book's location on the book-wall, many visitors scan the wall themselves with their eyes, naturally encountering surprises and new discoveries. To the extent that there is shuffling going on, wandering along the wall without the aid of a computer search is not uncommon both in my experience and in those observed of other users.

As the mezzanine level is only accessible by two steep sets of stairs, not everyone travels up them. In entering the room on the ground level, it is not uncommon to begin wandering along the ground level bookshelves. Here there are two aspects to note: One is that individuals scan the wall through a wandering process. This form of wandering is intriguing in relation to the mechanics of the RFID technology. Just as the mechanical RFID robotic scanners slowly move along the two levels, notably after hours nightly, scanning each title on each shelf, individuals scan the bookshelves themselves at their own paces and speeds, perusing for what titles might catch their eye. The second aspect to note pertains to casual readers, those pressed on time, or those with infirmities or handicaps who cannot ascend the provided stairs. Such circumstances either make the option of seeing "what's up there", along the mezzanine, moot or require asking for assistance of someone retrieving a book (in the case of a specified catalog search). In bringing all books on the upper level down to the ground I intended to make the books now only accessible by stairs, available within arms reach. Through the rotation, it would appear the books had changed in elevation as if by an invisible elevator lift. This runs in contrast to the physical movement people experience in the library predicated by climbing up and down steep stairs more often than not with the added weight of certain books in hand.

Part of the approach taken with the internal development of this RFID system is that it asks a public to re-imagine what the role of the librarian is in the 21st century. With the public invited to re-shelve books after research and because a book can be returned to any free shelf space, the frame of labor and job description changes for library employees. Clerks in this context are all but unnecessary. Staff are provided more time for personal research and are now able to focus attention on developing programming in the space to compliment the dynamic library, amidst other administrative duties and book work that precipitates through their change in relationship to a reduction in common physical labor. The way this RFID organization system invites the public to participate in returning books to the bookshelves fascinates me. It adopts the formation of an anonymous labor force (the public) in a context in which objects are tracked through technology that is being used more frequently today in contexts of security, surveillance in the context of citizens as civil servants and inventory in relation to the movement of product at global scale under capital.

Symbolically, the rotation as akin to cutting the deck in a game of cards (Abheben die Spielkarten), which comes after an initial shuffle. Such a gesture is traditionally applied as a way to reduce cheating amidst players; it is a clearing gesture.

As all these considerations inform a complex set of negotiations, there is also an internally quiet presentation realized. After the rotation, the library remained intact and looked as it did, unaffected, at a glance. The project exhibits the library itself as much as it changes it. The daily operation and function as a space of reference, search and study is not hindered through this project but highlighted by it. To the extent that the movement expresses a totality is quickly complicated in the moment someone began using the library for personal use post-rotation. Hereafter, the public use of the library commences in the deinstallation of the project. Through this inevitability of use, the library –as books, building, and institution– proceeds as affirmative dissolve. This exhibition, logistically and conceptually, remains accessible for view during the daily hours of the library to this day, yet in this context there is the mutual existence of the project being among the books themselves, of historical reference. The library, under its own conditions, simultaneously activates the project as it dissolves and deinstalls it. In effect, the installation was deinstalled through the continued use of the library through its operation as a reference space. This began almost immediately and would be the substantiation of a social engagement by the public.

The Sitterwerk organization proudly promotes this curious organization system tied to knowledge acquisition and production. The library raises very integral questions relating to the ways of how we find and locate fragments of knowledge as well as how we move them around and re-configure meaning. While a functioning library, it also has the qualities of a hyperbolic space where questions can be asked that apply to contexts outside of the room. The reason it is possible for this library to be functional and abstract has a great deal to do with the specifics of how a human body adjusts to the architecture of its design. What is peculiar is this: Somehow, each book supposedly becomes exciting and more flexible because you can move it, regardless of what information is inside each book. Does this new hypothetical liberty of the objects mean that the content (knowledge) is more flexible and thus also exciting? The books do not move by themselves; people move them.

There are many different places a book may be placed on the wall. Where a book is located is directly connected to the past movement of a person. However, the possible placement of the book is not the same as the possible movement of a person. With the book movement connected to each person's physical contact with the library, this activity quickly becomes the abstract factor through an elapse of time. I think this is partly because there are only a few people who are present every day, the people who work in the library. Yet even these individuals do not see every movement. In this library it is possible to imagine the books moving before you touch them. In this way it presents a haptic encounter. But this is not fantasy or a moment in which the books gain animism; this is matter-of-fact other individuals from yesterday, last month, last year rendered anonymous. What could be a highly specific pairing of two books physically touching each other due to independent research may be not be meaningful or at all recognized by the next person. The question: "where will the book transport me (in learning/knowledge)?" here comes very close to "where will this book be transported to?" The book-wall is not flat, it has traveled, it is traveling, and simultaneously is still a wall of gathered objects more or less similar in scope to the declarative dynamism.

A person's movement in the space is directly connected to the architecture of the room. The installation of the bookshelves and the creation of a mezzanine cuts the face of the library in two. In my project, the architectural order of the room in relationship to the body becomes an imposed categorical reordering of the books. This acknowledges two categories that are in fact present in the by-chance-order of the books: the ground level and the mezzanine level. The architecture produces an edge in the gradation process, folding the logic of the library as two halves. This architecture, which makes it easier for the body to reach for books, also divides the library into two horizontal units. A vertical rotation becomes a logical way to examine the much more complex and difficult-to-perceive anonymous movement of books because the changes are often small and over a long periods of time, made by many individuals who are abstract in relationship to the tangible books on the bookshelves I see with my eyes and hands.

There are numerous considerations which arise from the proposition of rotating the books. When a gesture is intentional, a sense of the internal logic becomes more transparent. When you begin to sense this contextual logic, you find there are new ways to move, more flexibility in negotiating what is present in a more critical way. Questions come from more and more specific observations of the structure and its context. Care and focus on the details sharpen as the abstraction produced by the gesture shifts. The rigid metrics of the proposal opens a malleable space for questions.

Sitterwerk has identified the cultural historian Aby Warburg's "Mnemosyne Project" as one inspiration for its "dynamic order". From what I came to understand, Warburg's project seems critical of historical indexing via linear and categorical framing. In praxis, he develops this criticism by encouraging subjective organizations of information to avoid formalized institutional hierarchies determining the placement of datas. He seems to be extending the artistic impulse into the field of art history, which does create some interesting problems. If a historian accepts the belief that an artist must be completely free to explore their intuition, this belief anticipates that the creative subjectivity that went into producing the artwork will eventually be objectively understood by the acquisition of art historical research and institutionalized knowledge. Warburg lived in a time long before cultural historians, artists and the public understood that art develops from categorical order and logic just as much as it does in presenting alternatives to logical forms. This is a complicated notion. Warburg proposes an alternative.

Understanding his project as an experiment and question and not an answer is important. He envisioned applying his method to the whole of human history as a visual continuum, which is less exciting conditionally than the soft impression of such a reality. The current popularity of websites like Instagram and Tumblr seem very close to Warburg's proposition. The concept that information is active becomes very important in such spaces. Arrangements of information create different concentrations of meaning but the information itself remains unaffected through these processes. The breakdown of creative subjectivity and objective organization has been a discussion for a long time within the production of art. Are critic, historian or curator the only people who can contextualize what an artist is making any more than the assistance provided in fabrication processes is occluded by the myth of singular authorship? Certainly not. Warburg challenges the concept that the production of art is a linear process by questioning chance pairs and the stimulus to knew unexpected discoveries.

One strong relationship between Warburg's project and the art library at Sitterwerk is a belief in conjectural knowledge. Further thinking on this bridge is needed. Recently, much of my thinking has been focused on proximities and interruptions. It may be possible to build a bridge between to examples, two points on the map. Each time we build a bridge, creating a link between the examples is a further grounding of them. We should also ask how proximal are these already to each other. How close together do they sit? One key difference I see between the Mnemosyne Project and library at Sitterwerk is that Warburg had a plan to apply his method to all art history. Sitterwerk is specifically unique as a library space because many thousands of books in its collection from the beginning were representative of the collection of one man, Daniel Rohner, who is now dead. The library thereafter became, in part, a presentation of Rohner's book collection as the foundation for subsequent growth. Consider whether this places Sitterwerk in a closer relationship to a cloister library than a modern library as a site of knowledge. Many libraries destroy or de-acquisition books each year to make room for new books. The architecture can hold only so many books.

One significant difference observed between the Warburg's Mnemosyne Project and the library is that Warburg emphasizes the visual reproductions (the images) from art history as image information and the rotation of the books in the library hyper-emphasizes, so as to make critical, that each book has a radio frequency I.D. tag which effectively transforms it into distinct objects of compressed information. Warburg's work expresses a decompression of the visual information; each image is free to move, not as an autonomous thing, but broken from linear forms of order. The library also requires these moments of example to create positive interruptions and re-focus the larger project. The rotation in the library is similarly a form of decompression as an action.

I should like to say, I am not actually interested in making artworks by my authorship. I do not name the projects I am involved in as artworks in a possessive sense. My investment is in specifically contributing to discourses relative to the production of art and framed by contexts of learning often through ethically driven inquiries. Primarily, this means I work in proximity, with and in sites of cultural education as well as in dialogue with individuals participating in these spaces. Most of my energy is dedicated to contemplating and analyzing the art production of my peers. This involves making myself available for dialogue to students, teachers, historians, critics, writers, fabricators, as well as self-identifying professional and non-professional artists. It is within moments of discourse between one or more individuals that my work occurs. These dialogues, which often take the form of long and intense conversations examining the complexities of artistic decision making, are not recorded by any direct means, such as photography, audio recording, or video. I find some of the most important discussions take place when the focus is the content of the conversation rather than the anticipated appearance it has on record.

The projects I realize function more like supplements to the discourse and dialogues I am engaged in. These develop from thought experiments that occasionally have the privilege of becoming material engagements. In this sense, the physical projects are secondary to the discursive praxis. They are footnotes. My work in the art world could be described as a set of supplements which attempt to engage the production of art developing in the space and time of discourse between individuals.

What might be referred to as distortion is not a tool I am utilizing for the project in St. Gallen. There are a few reasons for this. If we take a former project which occurred in this same library of turning all the books round on the shelves so the pages are facing outward and the book spines are facing inward, this form of rotation to the library is dependent on the visual impact it creates for people seeing it. The experience is in the first moment mono-sensorial, strictly visual. This distortion disrupts a person's ability to know what is inside each book because the written information like a name or the exhibition title is facing the wall rather than establishing a wall of art history. While this movement visually changes the library in a recognizable way, it does not effect the robotic scanners' ability to read the individual title information of each book thus leading to a bit of guess work to corroborate the location of a particular title after using the computer database. This appears to be an intervention which impacts a person's use of the library through abstracting the informational content of each book in favor of emphasizing a formal trait similar to all books there. It produces the semblance of an image at the expense of use.

To expand on the differences between an intervention and an interruption - In the example of the turned books, the intervention introduces a new order which directly affects my access to the library as a research source. The introduction of a new order is necessary for all functioning interventions, yet in this case the intervention affects people while the suggestive interference effects the library. However, in fact, this library, as a system, was not problematized by turning the books. More and more artworks are called interventions these days. At the same time, I am curious why fewer people are asking how an artist is intervening in the first place. Could we say, in some absurd way, that all exhibitions in which art objects temporally sit in a room constitute an intervention? The growth of a word's popularity is connected to its general acceptance. I understand an intervention to be an alteration which fundamentally effects an internal system of measure. I have observed most artworks described as interventions not actually interfering at all with an identified process constituting the facilities of exhibiting.

The paradox is, how can something be on display (meaning it is approved by some form of organization) and also be an intervention, meaning it exposes the inner-dynamics of this system of organization? What exactly is the confrontation in so many of these 'artistic interventions'? Whenever a gallery or museum or curator (or sometimes even an artist) uses the word intervention to acknowledge an exhibition or artwork, does this not indirectly express that the project has exposed no substantive inquiry or produced no extraordinary pressure whatsoever onto the normal order of functions? This authoritative acceptance threatens to flatten any kind of symbolic ideal the artist may have of challenging the actions of a powerful system through an individual act coming between the movements of this system.

Sometimes it is the artist who flattens the proposed complexity of the action. This may be due to a recent history of artistic intervention involving artists desiring to represent their actions as symbolically subversive while maintaining that the presentation of these actions is subjectively acceptable within the art establishment. But should not more artists now be examining the circumstances of this compliant behavior? The intervention in the context of art also has the problem that it is described as an artistic gesture. In some cases it is aestheticized where certain artists are inherently creating interventions in each and every exhibition they participate. When a methodology of intervention develops, a response system is created. This is a problem too often overlooked. If a person approaches a new situation knowing the tools of an intervention already acknowledged, or a host institution accurately assumes of what the artwork or an exhibition will require, there is very little actual complication to the space because this method of intervention then furnishes the interior of the space with quasi site-responsive decoration. Daniel Buren has classically abused this faulty platform for a long while after initially confronting certain underlying disparities at a systemic level.

Perhaps interventions are better understood when they focus on challenging art, not when they come from an artistic place. In this sense, manifesto groups in the early 20th century, at least in the beginning, are attempts of intervention. I really believe that the moment the intervention is modified by artistic sensibilities is the point where the changes which need to come into motion become confused with the fantastic appearance of the movements conclusion and/or success. This amounts to not much more than a visual interruption for a visitor facing the so-called artistic intervention. A dynamic visual change to the environment may only engage a set of relations to surfaces. Maybe we could call this pictorial intervention. These features continue to confuse me when an artwork is described as an intervention because there is no secret that a complex system never presents itself openly. Its interest is in protecting itself for longevity. When examining any so-called intervention, it is incredibly important to question what precisely is interrupted? Where are the interruptions located? In the case of the inward-facing turned books, this movement does not interrupt the actions of the library system, it interrupts people's access to it. This seems to me the shortcoming of turning the books in relation to an intervention. The library appears to turn away from me. It turns inwards. Now, I should say that I do not know whether that artist uses the word "intervention" to describe this turned book project, but it serves as an example of the inexact application of an artwork as an intervention.

In this project, I was attempting to reframe an occasion to consider the placement of various aspects: most prominently the rotation of the books in the library, but also the design of the postcard produced as supplement in the project, the placement of this postcard in the different libraries of St. Gallen, the public discussion which occurred in the first public hours after the rotation occurred, among other details. I do not think one of these is more important than another; all require careful consideration as supplemental to each other and their discourse. It may be that one of these aspects may appear more central because it is physically larger or more accountable as material. Yet this would be the constitute the initial conception of a hierarchy in meaning and production. If rotating the levels of the library appears to some as the limits of the project, is then the postcard only advertisement, the public discussion only an explanation? The rotation of the library plays with ideas of a hierarchy: The popular books collecting at ground level move up en masse to the top. The less accessible books above, or we should say the books which require more physical effort to reach, came in arm's reach when grounded. In a way, a situation where these independent articles (rotation, postcard, discussion, etc.) demonstrate a network of inter-movements. What is meant by this is that the textual and visual information of the project generates a series of acute interruptions, big and small, which establish bridges for more perceptive movements of books and movement of people within the context of this specific library.

Consider – when you move the mouse arrow on your computer to any hyperlink text or image to click and open it, the arrow becomes a gloved hand with finger. On the screen, this icon is a visual device to suggest touch and that we have access more information if we so choose. The hyperlink is active information. What happens if we conceptually invert these circumstances when we consider what is opened when we touch something like a book, when we take away a postcard? It is not only a surface that we touch. For instance, we also perceive the weight of the object in hand. I have for some years been very interested in how hyperlinks function and also the limits of this function. A hyperlink moves me from one location to another in a system of information. It holds an opening to this movement through a bridge, but interestingly this bridge is built for driving only in one direction. When I imagine a bridge in the world that is only for driving one way, the purpose of this kind of bridge is full of quandaries. When informational locations are hyperlinked to each other, what is established is a bridge or set of bridges allowing for multiple movements between to the points which connect to landscapes of context. Some of these would be: the logic of the rotation relative to the architecture, the dispersal of the postcard, the arrangement of the library relative to the movement, and the adjacent foundry.

In my dialogues with artists I have come to observe the use of abstraction in two prominent ways. They tend to contrast each other. One way involves making an image abstract through altering the contents of its encountered appearance, or what will be called the "picture picture". This process of abstraction involves abstracting some of the interior information in the found footage itself in order to bring attention, or pulling certain information in the image to the foreground while pushing other information to the background, if not removing it entirely. Information becomes differently isolated through this process. The exhibited image has been altered and is actually a new image because of this alteration. What is important to this process is that a person engaging with the abstracted image is now interested in this altered image, which means the person recognizes the image was already altered. Is it possible for this person to understanding the specific alteration as a device, somehow moving backwards to imagine the picture-picture? It is impossible to be precise here.

I think it's very easy to become lost and confused in this form of abstract gesture because it separates the process of abstraction from the product of an abstracted image. It produces what I refer to as vague abstraction. Regularly the artist makes the gesture privately and then exhibits the already altered image publicly. The abstract qualities are already locked within this displayed image, which we may describe in passing as "abstract". This could be an artwork in which the gesture of abstraction is used as reference to a technique from the history of visual abstraction...a way to create a static image that is read as "abstraction"; although, this historical quotation of style may not specifically lead to reading the content of the picture-picture in advanced ways. I notice many individuals end their interpretations on what the displayed image is historically akin to rather than how it differs from these associative references. Their process stops through categorizing the new image, rather than exploring it as an invitation to abstract thinking. Often I notice this way of abstraction produces an image which is unsharp.

The other employment of abstraction involves bringing specific current information into focus through examining what previously appears to be static. It is this very activity of research itself which makes this information flexible, moveable again. I am describing abstraction as a cognitive process. Abstraction here is an activity not only the artist has access to or performs to completion. Instead, one person or more sets into motion what other individuals engage with, not necessarily limited to physical contact but also in being thoughtful. The abstract qualities are not locked with the displayed image. They are developing through a person's perception, questions, and investigation. I am less interested in presenting an abstracted image and more interested in exploring how the image (picture-picture) is already abstract and context-specific in the same moment. In order to discuss a specific context we must realize the content is handled abstractly. Asking and considering the question, "What color is this here?" is an instance of active abstraction. In listening to the response, we should notice a reduction takes place. The information in the answer remains abstract but produces a static image: "Red." We move between these static and non-static forms of abstraction all the time. However, it is more often that people expect abstraction to be displayed in the artwork rather than realize abstraction is managed by their depth of inquiry. If a person begins to make observations of what is in front of them, eventually they will begin to wonder why it is in front of them. Everything stems from a choice even if an artist does not realize the millisecond decision occurring in the process of making it.

Within the rotation of books, the abstracted image one is asked to consider when they are entering is comprehensible in very simple geometry. I have chosen to isolate the two levels of the library and abstract them as two long rectangles, only after this could they be re-positioned. In the preliminary diagram, this is expressed when the red selection over blue switches to a blue selection over red. This choice to isolate the two levels comes to form the abstract materials of rotation.

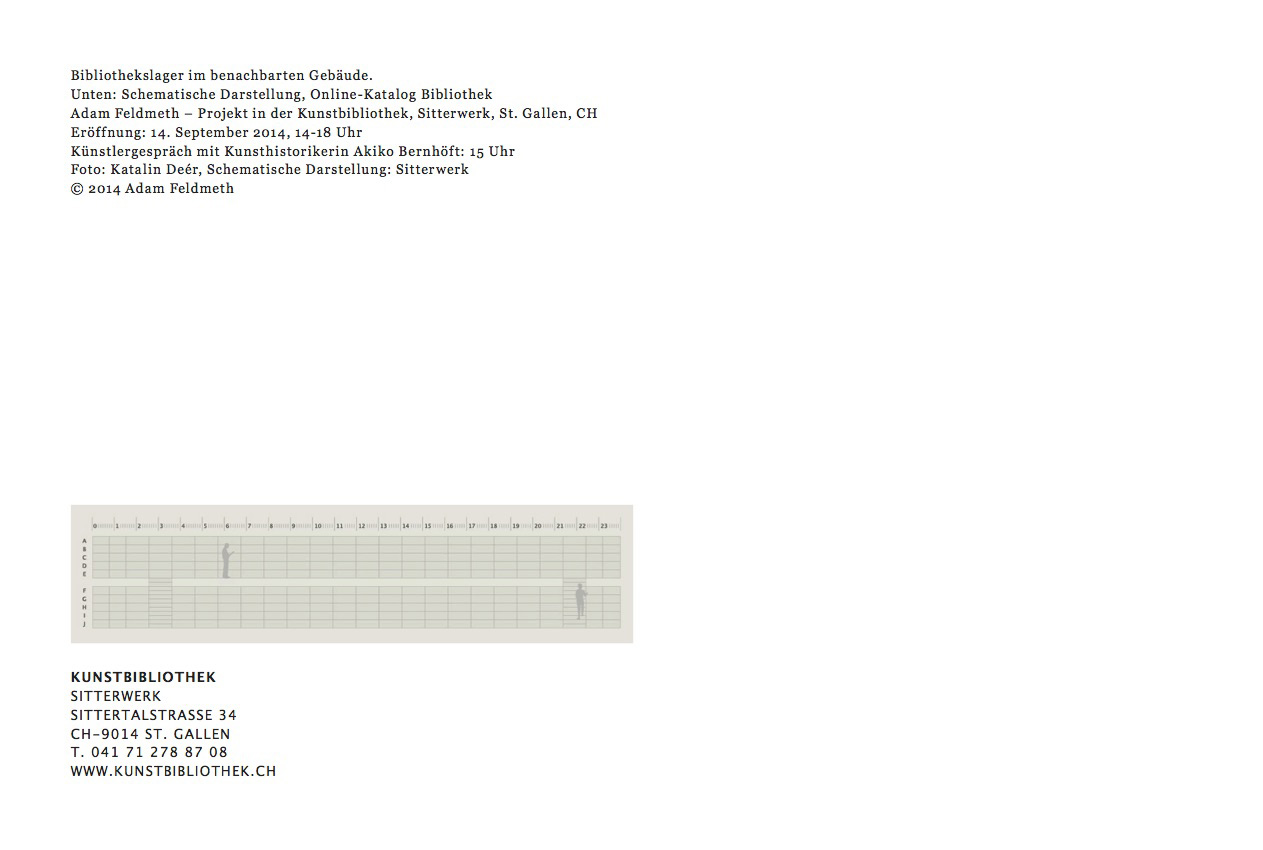

A postcard depicting library storage, the Bibliothekslager, accompanied the rotation. The placement of the image onto the postcard is an abstract movement itself as well as an acute inquiry. The textual backside of the postcard presented information which identified the location of the frontside photograph with additional information expanding upon access. The image represents all books in the library's collection that did not fit within its shelves effectively rendering them excluded from a dynamic order and public access. At the time of the rotation and upwards of half of the entire collection was housed in this storage space in another building located in the Sittertal complex.

The blue cock head positioned atop one of the green shelves is a test model for a Katharina Fritsch sculpture. There are a great many things there other than books in this room. Unlike the library which is to varying degrees navigable, this image of library storage is introduced through abstraction, limited to a single view point. The placement of the image onto the format of a postcard creates another entrance for considering the information as abstraction when the postcard is placed in the art library, and in the other libraries of the city and beyond.

Sitterwerk produces a number of postcards of the library, the material archive, etc. for distribution purposes. Some of these official postcards have views of the library and material archive which look to be in process from photographs made during the installation period or just after it opened to the public in 2006. The design of the additional Lager postcard formally related to these official postcards in some ways. It is the content of the image which shows the proximity of an art foundry where material is formed into art objects and a space of bibliographic research where images of artworks are reproduced in books. Somehow these reflect the early and late phases of an artwork, absent of the middle phase, the proverbial exhibition.

In effectively adding this image of the Lager to various postcards on hand, the suggestion was that the Lager was not touched by the physical rotation in the library proper. I hope this constructs a metaphorical bridge between Lager and library. Quite visibly, they are not the same, even though the Lager is not normally visible in the library or as an official image representative of the library. Therefore, the image on the postcard includes the area of the book collection which does not fit into the current dynamic order which is limited by the architecture. This is also why the Lager does not fit into the conceptual logic of the rotation. It is clear the architecture of the Lager is not the architecture found in the library. Of course, when this image is printed on a postcard it was touched by individuals and moved to different locations beyond the art library. The postcard allows people to indirectly pick up the entire Lager at once. As image, it is made almost weightless. This weightlessness is generated in part because the Lager itself is an abstract space in relation to the location of the library. A large percentage of the library is housed in the Lager, and from what I was told contained mostly books on photography and architecture. In contrast, the physical weight of the books in the library building is emphasized through the direct movement of all those books.

Interest in producing an alternative view of the library was connected to this advertisement function already used by Sitterwerk. The dimensions and some early design elements remain similar to the official postcards; however, with the frontside image being an alternative view of the library, the text side needed to likewise be alternative in some way to the standard in-house design. "Bibliothekslager" in the top left corner is an extension of the original design. Because this storage space is in fact a large part of the book collection of the Kunstbibliothek, it is important that the address in the bottom left corner name the "KUNSTBIBLIOTHEK". One early idea was to change this to read "KUNSTBIBLIOTHEKSLAGER" or something similar to this yet in studying the Sitterwerk organization, this idea was not productive because this storage space is not identified as an named location within the institute. Not in the way "Kunstbibliothek" and "Werkstoffarchiv" are proper names which represent the different departments of the institution. "Bibliothekslager" is what the storage space is informally called, but it is not an official name.

Library locations listed by the "Buchstadt St. Gallen" organization helped to determine what additional library locations the postcards we installed within. Buchstadt St. Gallen is an organization invested in enriching the cultural presence of the city within the greater region and country of Switzerland through acknowledging a long (1,200 year) historical relationship to book keeping. The interests of this organization are connected to promoting the city as a tourist destination. It is this reality that Buchstadt St. Gallen operates as a part of the local tourist industry.

With Sitterwerk and the Kunstbibliothek already connected to the Buchstadt network, the postcard has a non-arbitrary form of initial dispersion at a municipal scale. An official Sitterwerk postcard at any of the other library locations would function as a form of acceptable (solicited) advertisement for a neighbor institution. Distributing the postcard only to the other libraries in the Buchstadt network places one of these postcard in the context of organizational tourism whereas placing the postcard in a cafe keeps it in the context of cultural things-to-do about town. The kunstbibliothek serving as a tourist site is quite different from an art historian traveling specifically to St. Gallen to work in this library for research. For a citizen finding the postcard designed for this project inside another city library may stimulate questions of storage and access in that location, not only at Sitterwerk. They may be curious to now visit the art library or visit again to inquire about this unacknowelged Lager.

If a tourist is visiting the city for the diverse book culture they may begin to see this postcard again and again in each library they enter. As it is clear on the map, Sitterwerk is the most isolated and distant library location in the Buchstadt and greater library network. Through distributing the postcard in all city libraries the intent was to present an alternative presence for the Sitterwerk as introduced through its non-visible side. In addition to working with some of the original elements of the Sitterwerk advertisement logic, which is most clearly expressed in placing the postcard in the Kunstbibliothek with the official postcards, the postcard can also be understood as an object of tourism as well through its placement in these other library spaces of the book city and as takeaway of the project. In these various locations, the postcard was installed next to other local advertisements, postcards, etc. for current culture in the city.

Another notable detail on the backside of the postcard is the gray schematic of the library. It sits on the left side of the postcard between the contextualizing caption and the address. In one way, this schematic represents the architectural arrangement of the library that has inspired the conceptual proposal for the rotation. It is also quite apparently of architectural difference to the Lager. We see this schematic elsewhere only when we search for a book in the online catalog. In standard use on-screen, we see a red mark where the book is located based on the last scan constituting digitized order. When a book that is then located in the Lager is searched for, this schematic does not come up. Instead a message appears: "Die Position dieses Buches konnte nicht ermittelt werden. Gegenenfalls befindet sich das Buch im Lager. Bitte wenden Sie sich an die Bibliothekarin."

It is logical that the schematic of the library would not be present in such a search result when the book is located in the Lager. What is fascinating here is that the place of the schematic image on the computer database is replaced by text requiring a user ask for assistance to retrieve said item. "Lager" is text here: The image on the postcard further describes this "Lager". Again, the completely gray schematic is an impossible image to see online because every time one sees the schematic, it included a red mark representing a book. And when a red mark cannot be placed on the schematic because the book is located in the Lager, one receives the text message in place of the schematic. An alternative to this text would be a schematic with no red marks. In a sense, this would express that every book in the Lager is not in the library scan. The textual notification indirectly imagines a gray schematic without making it visible.

This decision to include the gray schematic also helped to answer which typefaces were applied to the postcard. Earlier, I had hoped to produce an exact copy of the Sitterwerk logo address text and was planning to work with the in-house graphic designer to discuss this possibility. This would have meant the same layout, same font, etc. With the gray schematic in place, the postcard had established a link to the online presence of the library through the terminal interface. With the schematic being an image one only sees on-screen through online searches in the library catalog this made me reconsider the back of the postcard in relationship to the digital look of the library. Whereas the official font of the library in all logo and published text (postcards, annual reports, etc.) is consistent, the fonts used for the webpage maintain a different consistency. The Georgia typeface is used for all information text and "Lucida Grande" is used for all link texts, known as button-links. Georgia is a serif font while Lucida Grande is a sans-serif font. These two fonts provided a way to continue an alternative view of the library in the space of the postcard. The address in the bottom left corner was grounded in Lucida Grande and the caption in the top left corner was in Georgia. With these fonts and the gray schematic all content on the back of the postcard takes its formal cues as information from the online database and institutional website while the placement of this information comes from the logic of an advertisement and tourist postcard.

The right half of the postcard was left open of any printed information. If a person wanted to send the postcard to someone else by post, it was entirely possible, though the design did not explicitly encourage this. In other words, the postcard functioned as advertisement for the Kunstbibliothek within Sitterwerk and the project while also as an object of tourism when dispersed throughout neighboring libraries within St. Gallen. How it was used after by individuals remains a question of such ephemeral production. Perhaps used as a bookmark to hold a page in a book.

The library at Sitterwerk describes that its RFID system produces a dynamic order in the library. Dynamic in what way(s)? This question brought me to researching among other topics: Dynamical systems theory as well as the Italian Futurists' concept of plastic dynamism. Constant change, activity, progress is one dictionary definition. The change in this context of course is not perpetually constant; there are moments when the books do not move each day and sometimes longer. Activity, yes, but this importantly requires human interaction. The books do not move by themselves. Are people part of the library because they interact with it? At the end of each day I leave the library; I do not bring it with me. Progress is a complicated idea. It is not the RFID system which is dynamic or the different books in the collection. Sitterwerk specifically refers to the order as dynamic. In press language, I hear "dynamic" also meaning "exciting" and possibly "radical". I do not know about any of this. I did observe that the immediate interactions people have in the library are close to a form of entertainment. They are excited to play with this granted liberty of mixing things up. After a time though the entertainment ends and the flexibility of the library becomes helpful in just restocking the shelves with books without looking where you place them, because the robotic scanners will read the location of each book, no matter. A sort of blind, arbitrary process. So, it is important that new people with fresh eyes are rotating through the library and that the books are rotating about. If people stopped coming or books stopped moving, the order would be questionably dynamic. Again, I return to imagining a day no one enters the library, maybe on a Tuesday. The books were scanned Monday evening, not one book moves on Tuesday, and the books are automatically scanned again Tuesday evening. What kind of process does this represent? It is very interesting to consider this.

If it is the placement (and re-placement) of the books that produces a dynamic, then this does not mean the books are dynamic themselves. It is the order created when they sit together on the bookshelves which articulates this dynamic order. I think the order is what we see first as a library, a wall of books. The dynamic quality to this visual order is the movements made by people, which fracture the past order, scanned the night before, which then prepares for a new order when the wall is scanned the next night. A succession of orders. Even though the library is visually a big mix of art history, the robotic scanners each night virtually reduces the big mix into a specific order that is not a mix. Add to this individual researchers who make small curations in the shelves, bringing together a few books which are folded into the objective scan and the larger public mix. A library is the building and it is also the collection of books. If I am leaving the house and I say, "I am going to the library." This conveys what? That I am traveling to a building with a street address and also probably entering this building where there is a collection of books. A library is represented in the architecture and in the collection. By contrast, if I am going to the museum, this does not equally refer to both the building and the collection of objects within it. We could say the artworks in a museum make the museum, but normally we refer to this as the museum's collection. Or that we enter the museum to interact with artwork. Not everyone directly interacts with the museum in the museum, though everyone does indirectly interact with the architecture within it. After I enter a library (architecture), I then interact with the library (book collection). The art library at Sitterwerk intensely emphasizes this interaction. In this way, it is a very experimental space.

If we return to this idea that constant mixing generated by human use establishes the reality of the dynamic order, the isolated pressure of the rotation was to the structural frame between the architecture of the library (which holds both people and the books) and the mix-scan process (locating the collection). While the collection of the library is always moving and mixing, the architectural library is fixed. The most visible architectural feature is the horizontal division to the collection through split levels and the wall which produces a ground floor and a mezzanine above. This does not technically establish a new floor in architectural terminology, but could be described as an intermediate floor. In other words, the mezzanine does not divide the room into two smaller rooms. These two levels share the same common ceiling. An intermediary level does however produce the feeling of a lower ceiling when you stand under it. In this case, when you are looking closely at books on the ground floor of the library you are standing directly under the mezzanine. This architectural division of the visible collection also determined the need of two robotic scanners, one for each level. The architectural addition to the prior interior space of the former structure is directly connected to the library; it constitutes it architecturally. It also directs how a person gains access to the visible collection and moves in relation to it. In order to find, locate or discover higher level books, a person must walk up the stairs. The logic of the rotation adopts these dynamics of the library architecture and imposes the next order of the library collection.

Prior to the rotation, I did not know what exact appearance the library would have in that moment. Similarly, I did not know how the library would look just after the rotation. Producing the rotation reveals more about what the library looked like before the movement than any visual distortion after. I am not certain if the rotation modified the visual presence of the library; however I do think the way an individual experiences the library could be augmented due to this interchange of its levels.

As previously noted, the mezzanine level contents move around less than their ground level counterparts. To be clear, there were areas on the mezzanine which have not entered the process of mixing between the library's start in 2006 and 2014. Moments when a number of Mark Rothko books on the mezzanine are next to each other on a shelf is a representative of an older alphabetic order utilized in the library before the RFID system was installed. Why have these books not moved in all this time? This could be due to a number of conditions: It could be that Mark Rothko has not been a useful name for people using the library; Rothko may not be a subject of research in the last years. It could be that because the Kunstgiesserei is focused on sculptural forms and due to this the most frequent use of the library has been concentrated in what could amount to a history of sculpture.

The repetition of the name could arise from a previous researcher working on Rothko who gathered together all books baring his name; this person could have curated them together as a group when returning these research material to the wall. And then there is the fact that they are installed on the mezzanine level, which is less frequently wandered. When the mezzanine is explored and a person carries the book down the stairs for more serious study, it is most likely re-entering the bookshelves on the ground as previously noted. Through bringing all books from the mezzanine down as a set, a number of these conditions open way for questioning whether there are certain conflations being made. The most pronounced question that I can think of is, what does the mezzanine look like when I step back from it?

The floor of the mezzanine is 81.6 cm in-depth. One augmentation made by the rotation is this group of Rothko books (previously on the mezzanine) thereafter gained an additional amount of floor space. A person will now be able to step back and view the "mezzanine" from the center of the room after it was brought down to the ground. It is possible to see the architectural mezzanine from the center of the room, but then a person is also needing to look up to see it. There is always an impossibility of standing eye-level with the architectural mezzanine from a few steps back.This distance feels larger in part because you have to climb the stairs to get close to the content of the mezzanine. The moment you are on the mezzanine, however, you become unable to step back to notice internal compositions and the lack of thorough mixing. The mezzanine floor you stand on is materially composed of the same wood found on the ground level. Through the rotation, the converse of maximizing the floor space for the prior mezzanine is the minimizing the floor space for the prior ground floor.

As the majority of interaction with the library seems to take place on the ground floor, would this still be the case after the rotation? If dynamics hold, it would be sensible that in time the ground would again be the more active half. Though initially this will be stimulated by an entirely different set of books. It is possible to identify certain books on the mezzanine when looking up from the ground due to large spines and/or bold typefaces. If some kind of popular concentration of art history has developed on the ground bookshelves over the years, will these titles still be popular or moved as frequently on the mezzanine? This is one effect of intended interruption I aimed to produce to make way for inquiry. If certain books are more frequently in use, what could be called, popular here in that the name of an artist is more recognizable, these books, or names, or associations of artworks or praxis tethered to them will eventually coalesce at the ground level. It only takes one person to bring a book down from the upper level to make it easier to come in contact with for everyone else.

When I am personally researching in the library, I am not creating associations between two books because of the names printed on the sides. I may however be using the names or books I do recognize to locate names or books I do not recognize around it. Often popular means famous. And just like certain individuals feel close to a certain Hollywood actor because they see this celebrity's face so often, this celebrity can begin to feel more accessible due to ease of recognition. The same could be said of people engaging with art history. You return and search for new material or viewpoints on the artists and ideas that continue to hold some gravity of attraction for you. Because the Sitterwerk collection is not gathered together alphabetically, a person really does have to move around the shelves to find what is familiar in this way. And so we also find what is unfamiliar. What amount of investment does it take a person to randomly find an unfamiliar book or artist and then seriously study the content inside?

There is the suggestion of exposing a visual hierarchy through the rotation. If more books on average are touched and moved at ground level, would this be an indirect indication that this subject matter is then more popular than the upper half of the collection? They are certainly more easily accessible in terms of bodily access. What does it mean for less accessible books on the mezzanine to be more easily accessible on the ground after the rotation? This doesn't inherently make them popular. It may mean they are more frequently moved after. It may push more people to ascend the stairs to reach subject matter of popular interest.

What is interesting to me in relation to this RFID system is how the movement of a book does not always correspond to a person opening this book. The mechanics of the RFID system do not recognize the book, but the bibliographic data stored on the chip, the intelligence tag, fixed to the interior of the cover. Because a person is unable to observe radio-frequency waves, the general translation of this system involves understanding each book as an independent object. This means that the RFID system here does not read what we see and we do not see what the system reads. In most cases, these objects contain documentation and analysis of art realized in the world. Some books may also represent this reality. All these books however have a way of suggesting that the art referenced in them is historical. The art publication in this sense is some form of fast pass to knowledge because it is on record. If an artist tomorrow donates a book on their artwork to Sitterwerk, this artist's work is touching the matter of art history. In actuality, one book is just touching another one. Two artists names literally coming closer to each other on the shelf does not imply anything inherently meaningful. Automated scans accounting for physical proximity do not render such proximity automatically symbolic.

For this system to be open, there are certain decisions which establish limits. There is a dimension of this project that is invested in labor. This is perhaps most emphasized in the physical movement of books, necessarily by-hand. I tend to think of the most frequent activity a person working in most any library engages in: the re-shelving of books. While anyone on the library staff may participate in this, a job description only involving re-shelving books would usually be given to a library clerk, a form of clerical work. The library at Sitterwerk removes this position altogether and thus greatly lessens the amount of staff labor bound to this activity. Sitterwerk establishes a model in which it becomes the responsibility of the public to clear the workspace when finished with research.

It could be imagined that this frames a form of trust from the institution towards its patrons. This leverages this internal, institutional and otherwhere employee-based task onto the public. In any other systematized library a book would have a precise place. An employee would get to know the library in such a way that returning a book to a specific place would be second nature, though making certain it is in situated exactly between its neighboring books on the shelf requires more concentration. Like the shift which occurs from happening upon the street of a certain house address to then moving more slowly to locate the exact house number. Through the rotation, each book was given a specific place to go. For most any other movement in the library, while changing the address of a book could be intimately and subjectively important, it quickly becomes arbitrary in relation to the rest of the mix.

It seemed that the physical act or the complexity of the conceptual structuring was never fully apparent in the presentation. The consideration and labor involved in art production are usually not made explicit to the public unless this information primarily represents the project itself. There is always some compression which takes place. One significant thing that is specific to the context of this project is that the environment is not designed exclusively as an exhibition site in the ways a gallery or museum are zoned for. When we walk through an entrance labeled "Museum" we make certain micro-decisions preparing ourselves for a relative experience of encountering artworks. When we walk into a library, unless we enter with the intent of viewing an art project we heard about, we come to engage with knowledge, and in this particular case, things of an art historical record. Visiting the compiled documentation of artworks and exhibitions through history is not structured by the same decisions.

I asked myself many times in preparation for this project whether the project generates a space of exhibition. Is not the normal dynamic that we visit spaces of exhibition to see art? The question of whether an exhibition generates art is an intriguing one. Many artists do depend on coded exhibition spaces and make artwork tailored for them, whether intentionally or unintentionally. For this project, I chose a space which does not necessarily function as an art space in the way an exhibition functions. More precisely, the presence of most of the artwork reproduced in the books also represents the documented artwork was previously exhibited (elsewhere). We might say an art library is only possible through the exhibition of artworks elsewhere which eventually generates documentation of the exhibition as an event in the case of an exhibition catalog or stimulates other academic forms of scholarship. This has anyways to-date been a predominant model in the accreditation of culture.

It is not possible to neglect the close proximity of the art foundry, both in its geographic adjacency and in its organizational relation to Sitterwerk. Here is a space where artworks move from an abstract concept to a concrete materiality. This space itself is not an exhibition space but a point of process before something enters one. Artworks made there are quite often sent directly to these exhibition spaces in the next phase of a processual provenance. There are some books now in the library which have documentation of artworks produced in this very foundry. This indicates some form of return in what could be considered this typical linear progression of acculturation. Following the development of an artwork in a process places the exhibition not as the end of production or the thing in-itself. It is only a momentary pause somewhere in the middle. The image of the Lager with the Katharina Fritsch blue cock's head provides an interesting alternative to the seeming extremes of material production and analytic digestion.

Exhibitions tend to hold the most temporary of positions in this arrangement. An artwork can take years to produce. Understanding it as a contribution can take even longer. It would seem that certain artworks bound to the exhibition are by the circumstances temporary themselves. I would be careful to recognize here that these artworks are not temporary, but because the exhibition is temporary, these artworks are designed to "close" when the exhibitions close by accepting these parameters. When might this project premised in rotation "end"? Does this suggest that the project is not directly aligned with the temporality of an exhibition timeline? I have always understood earnestly site-specific projects to be temporally sensitive as much as spatially sensitive. Somehow most projects described as such go for the space, and perhaps this is because it is within the concept of space that a sense of display is more tangibly established. Comparatively, it is most often the privilege of museum guards and gallery staff which experience the temporal expanse of an exhibition. The vernissage and finissage are interesting markers to consider because even if both are not represented by an event in every exhibition, they mark the limits of an arrangement of objects in space of display. The vernissage and opening of the project at Sitterwerk corresponded to the standard open hours of the library on Sundays, 2-6pm. The means to create an event do not necessarily equivocate an exhibition.

The logic of the project may be self-effacing in the sense of producing a massive material work so close to an art fabrication site which will never leave for an exhibition elsewhere and so close to the ostensible material of art history in process which immediately dissolves through its continued engagement. This project was not trying to generate a space of exhibition in the absence of one. An intervention might do this. Instead, the inquiry was in the ways supplemental material, such as a press release, a postcard, an conversation talk between artist and art historian can lead to the sense and image of exhibition, the missing step in stabilizing the accreditation of culture. The exhibition we experience is clarified by these, just like the fabrication and documentation are essential in presenting the material reality and physical installation in the context of art in the world. All matters of the project as equally important when an awareness of how these supplement are structuring and contextualizing the presentation is considered.

For some time, I've been reflecting on the many exhibitions experienced through press releases and installation photographs. Sometimes we have been to the gallery before, many times we have not. It is now possible to view visual documentation of an exhibition during the same time the exhibition is installed somewhere in the world. There are extreme cases of galleries that publish these images on their websites the same day as the public vernissage. This is rather different from a time when studying images of exhibitions in a library was the primary means to process their past realizations. Often there was only one or two images to express its interior environment. The temporality of the exhibition is not only demonstrated by the date of the show but also by the post-production of the book itself. If there were interior views of the room in an exhibition catalog, this means the book was produced after the exhibition opened, and most often was not in print before the exhibition closed. How does having access to documentation effect the physical encounter of artwork in the room? This seems to make the exhibition more interstitial as experiential reality. That the room looks like an exhibition space in contemporary online documentation still seems important in providing a backdrop in the image. It becomes now a matter of placing and positioning objects and materials in certain arrangement which are subsequently emphasized through the distance of the images as artworks in the documentation.

Consider if an artist is anticipating that a larger audience can immediately see the documentation, not as a secondary experience after the show, but as a primary experience itself. The temporal installation of the artwork in an exhibition now may be little more than a photoshoot. A moment when more documentation of an exhibition is shared online, the more seemingly important that exhibition is in the social world of art. And this increased interest in the exhibition does not inherently imply more people are traveling to see it in the physical sense. Perhaps this is due to an exhibition being halfway around the world or because the images on a computer screen are enough for a show in town. Will the rotation be visibly perceivable in the photographic documentation? If it is not visible does this reflect back on the exhibition being not visible? Questioning the formats of presentation become as necessary now as highlighting the containers of display.

The physical act of moving the books was minimal in comparison to all movement the library has experienced before the rotation. Perhaps in consideration of the limited time for installation this comment seems egregious, but grounded in the continual use of the library, this is not an enormous move. Unlike a room with a regular program for temporary arrangements of artworks, the library has no moment when the room is "clear" between exhibitions whereas in a museum or gallery there are these instances. Perhaps the hours the space is closed in the night could be said to be clear times, though museums and galleries function on similar spectrums of public access and this library's capacity to host visiting scholars who reside in guest quarters of the library itself make it accessible for after hours use in such circumstances. The moment between the deinstallation of the last exhibition and installation of the next exhibition is difficult to place in this context.

Placing too much dominance on the physical act would be wrong. Yet, the focus of the project should not be perceived as an exclusive performance. In a sense, this means the labor is just a necessity of the rotation. No more than moving our feet is a means of getting somewhere. A question of whether this labor would be accomplished by professional movers came up. How would this augment the dimension of the physical act? I soon realized that this course of action was both conceptually impractical and ethically complex.

Professional movers may be required to install and deinstall artworks, and similarly are a helpful service when trying to "move a house". Quite different from art installation, anyone can touch books referring to this artwork. This is a two-fold meaning for the project. With the necessary labor being realized at an individual scale, rather than by employing a service, the rotation is not a grand gesture or realized through hired external help; it is by comparison feasible without. Through its realization, the rotation becomes just another group of books moved in the library over time by an individual user. This movement of books may represent a form of specific research through this physical act. In the art foundry, labor involves an undeniably physical act. The weight of the materials used for a sculpture matter because this may impact the way the sculpture needs to travel or be installed on-site elsewhere. These materials are almost always used in high quantity and are normally very heavy: plaster, bronze, concrete, etc. In this sense, the rotation was a metaphoric fabrication.

The second fold created through the realization that while only some individuals touch art, anyone can touch books is activated through an acceptance of the project's inherent dissolve. Within the context of the project, books become material in the work. Observation of a visibility/invisibility quotient holds purpose here. Through continued use of the library, members of the public touched, moved and opened the contents of the visible collection because it is within their right to handle the books in this context. It is possible the rotation may have accelerated this handling. The intriguing question is whether this simultaneously implies that the public continues to touch, move and open the project, which might be referred to as an artwork. “Opening" here should be taken to mean, understanding or accessing the conceptual investment and implications of the project. If accessibility requires visibility, then this will need to come from a person studying the library before reaching into it for research material to study with.

Every book has a mass weight. A heavy exhibition catalogue or coffee table book is something we immediately feel when we gather this weight. Sometimes we anticipate the weight of a big book before we hold it. "That's a big book!" also could mean “It looks heavy!" Many books though do not craft much anticipatory consideration in relation to weight. These are questions that library designers and structural engineers have to keep in mind. How much weight in the form of book-matter have you carried in the last year? It adds up over time. There was a strong bodily experience after the rotation when a person stood close to the bookshelves. It is perception of this bodily experience which remained more integral than imagining what it must have been like to move all those books in an expeditious turnaround. I cannot control how a person searches for such reason, but I would prefer the sensitivity of the body to be considered in the experience of the present moment. The past bodily efforts immediately become abstract within the design of the dynamic order at Sitterwerk. This includes all physical actions towards realizing the rotation.

There is not one book in the library which provides further information on this project or presents the rotation secondarily as documentation while the project was recorded in every book then present. The books became a form of documentation of the rotation. What remains of the rotation becomes an example of a material archive itself, as well as material that cannot fit into the material archive at the other half of this room shared by the library.

If tactile contact with a book clarifies an indirect contact with art documented on the pages, is it logical to imagine that emphasizing this tactile contact with the same book could clarify a direct interaction with art? Just as in the case of someone more comfortable viewing an exhibition on the computer screen than stepping through the door of a gallery, what happens when the presence of art production links this distancing effect? With all of the art available in the form of information in the library, it is safe to state that it is not physically in the room at the time of research. It is somewhere else in the world at the time you sit down and open a book. It may have even been produced inside the art foundry, through a door only 8 meters from the library's entrance. This indirect contact may make art easier to handle on a discursive continuum. The work is a catalyst for a discussion.